As recent data show big rise in youth suicide rates, states are launching, mulling new prevention strategies

Newly released federal data on suicide rates among young people show a disturbing trend that many state lawmakers already know too well because of tragic stories in their own legislative districts.

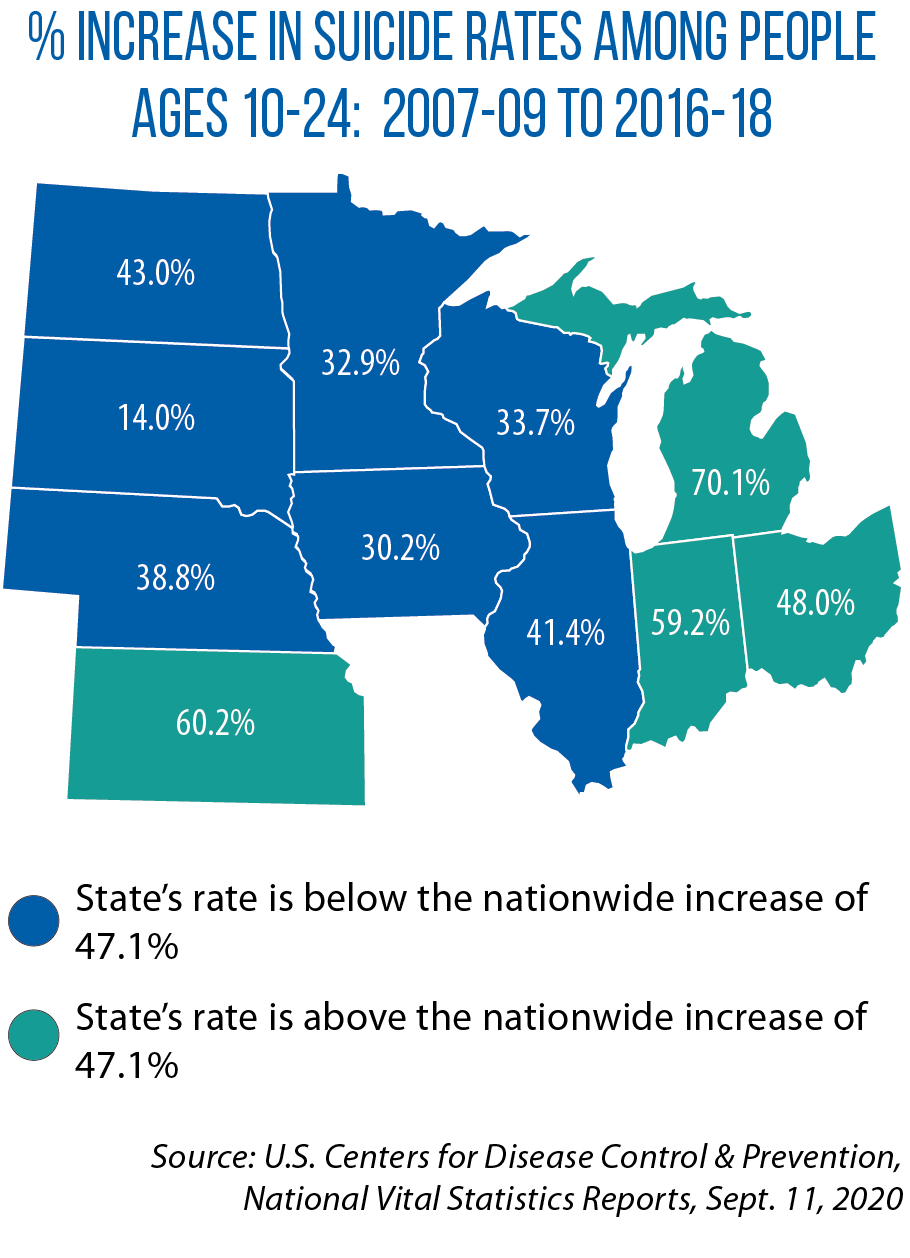

The number of deaths rose dramatically over the past decade — by 47.1 percent nationally — according to research from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which compared suicides among people ages 10 to 24 between two time periods: 2007-2009 vs. 2016-2018. In the Midwest, rates were even higher in four states (see map).

How can a state better help young people and reverse this trend? In Wisconsin, a legislative task force formed by Speaker Robin Vos began exploring that question in 2019.

Led by Wisconsin Rep. Joan Ballweg, chair of The Council of State Governments, the bipartisan panel in Wisconsin held a series of hearings across the state. That led to the filing of nine bills designed to reduce the state’s suicide rate; two of those measures became law this year.

Under AB 528, the state is starting a $250,000 grant program for high schools to launch peer-to-peer suicide prevention programs, which Ballweg says legislators learned are likely to be “much more successful with young people” because they’re more open to communication from their friends than from adults.

The second new law, AB 531, requires contact information for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline to be included on the student ID cards issued by schools and the state’s technical colleges and universities. The ID requirement is based on a California law, Ballweg says, and was suggested to the task force by a parent whose daughter lost a friend to suicide.

Among the task force’s other ideas:

- establish a suicide prevention program run through the Wisconsin Department of Health Services (AB 525);

- provide new grants for local suicide-prevention organizations (AB 530); and

- require two hours of continuing education on suicide prevention for physicians, psychologists, social workers and other health professionals (AB 526).

That only two bills became law “was a function of coronavirus” and the limits it put on the 2020 session, says Ballweg, who was chair of CSG’s Midwestern Legislative Conference in 2016. She hopes for further legislative action on suicide prevention in the weeks or months ahead.

Other examples of recent legislative action include Michigan’s new Suicide Prevention Commission. Created by SB 228 (which became law at the end of 2019), the panel is researching the causes and underlying factors of suicide in Michigan. It must file a final report — including a list of evidence-based suicide prevention programs — within a year.

Saskatchewan’s Ministry of Health released a new suicide prevention plan for the province in May. That same month, Ohio senators passed SB 126, which would allow crisis assessments of minors by mental health professionals without parental consent if a professional believes the minor may be suicidal or a physical threat to others, and if the parent is unavailable. (SB 126 was still in a House committee as of October.)

Ohio’s HB 502 became law in 2019. It requires biannual training on suicide prevention for some school employees. Training has been required since 2013, but without a specified frequency.

Jon Davis serves as staff liaison to the Midwestern Legislative Conference Health and Human Services Committee.